The Unalachtigo of New Jersey

"The Original People of Cumberland County" (PDF version)

Anne Schillingsburg Woodruff and F. Alan Palmer

Table of Contents

Foreword

Original People of Cumberland County

About the People

The Nations

Picture: Map of New Jersey

The Land of the Unalachtigo

Lenni Lenape Food

Shelter

Transportation

Pottery

Tool Making

The Departure Of The Unalachtigo

Picture: Lizard Stone

Picture: Clay Pots

Picture: Arrowhead and Spearhead

Picture: Grooved and Ungrooved Axe

Picture: Gorgets

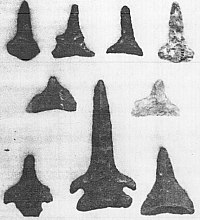

Picture: Drill Points

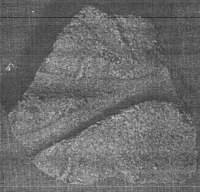

Picture: Blade & Scraper

Picture: Net Sinker

Picture: Banner Stones

Picture: Shaft Smoother

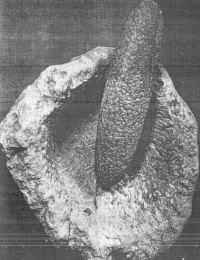

Picture: Pestle & Mortar

Picture: Bone Implements

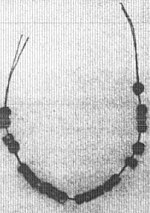

Picture: Beads

Picture: Pipes

Acknowledgements

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Foreword

This booklet is not intended to be considered a scholarly treatise on the history of the Lenni Lenape Indians of New Jersey, but is primarily an introduction to those Indians of Southern New Jersey whose personal possessions now form the collection of artifacts accumulated during the lifetime of George J. Woodruff.

Top

Original People of Cumberland County

One fine autumn day a ten year old boy and his mother were picking up chestnuts across the road from their home in Woodruff, New Jersey, when he found an arrowhead among the leaves. His mother explained that the Indians had once lived in the area and had made such arrowheads for use in their hunting. This sparked the interest in George Woodruff that led to his lifelong hobby of collecting Indian artifacts from all over southern New Jersey. He became an authority on the subject and was a charter member of the Archeological Society of New Jersey which was formed in Trenton in 1937.

The George J. Woodruff Collection comprises 20,000 specimens displayed in a museum which is open to school groups, scouts, and any interested organizations.

A very real factor in the success of anyone hunting Indian artifacts is knowing where to look. The Indians located their villages and campsites near a stream where transportation was readily available. We have learned much as to where and how they lived by hunting and digging along the streams of this area. These include the Cohansey and Maurice Rivers and their tributaries, which flow out into the Delaware Bay.

We are able to find evidence of an encampment by locating fragments of pottery and fireplace stones. We look for chips of stone, rejects, and problematical materials (unfinished stone artifacts). Surface hunting is easier when a field has been freshly plowed, and especially after a soaking rain. While it may be true that Indian artifacts are more difficult to find today, the Indians lived in Cumberland County for thousands of years, and their artifacts are still being found throughout the area. With interest and determination anyone can become a collector of tools or implements once used by the "Original People of Cumberland County".

Top

About The People

The Indians who inhabited New Jersey at the time the Europeans came, called themselves Lenni Lenape, which literally means "Men of Men", but is translated to mean "Original People". The English colonists called them "Delawares", after the river and bay along the banks and tributaries of which most of them lived.

The Minsi or Munsee (People of the Stony Country) lived in the north. The Unami (People Down River) lived in the central part of the state. The Unalachtigo (People Who Live Near the Ocean) inhabited the southern part of the state in an area extending from just north of Camden, across the state to the Delaware Bay.

In this account we are most interested in the Indians who lived along the water courses of the Cohansey and the Maurice Rivers and along the shores of the Delaware Bay. The Unalachtigo were a peaceful, industrious, and quiet people who established relatively permanent villages, leaving them only in their quest for food or furs.

We are told that all Lenni Lenape were somewhat similar to one another in appearance; most of them were of medium height and their bodies were well proportioned, slender and straight. Their hair was coarse and black; their beards were scanty. Their teeth were of medium size and very white.

Early records indicate that the Indians of New Jersey had an excellent memory, a lively imagination, genuine wit, natural understanding, and were very curious about things that were happening about them. The inherent skill in using their hands is evidenced by the beauty of the workmanship shown in each delicately chipped arrowhead or elaborately decorated piece of pottery which has been preserved to the present day.

For the most part, the Unalachtigo were not a warlike people, no doubt because there was little reason for intertribal conflict. There were probably never more than 10,000 Lenni Lenape living in the entire state of New Jersey. At the time Cumberland County was settled, there were perhaps 600 Indians living within this area, occupying villages along the Cohansey River near Greenwich and along the Maurice River.

The three nations, the Minsi, the Unami and the Unalachtigo, each occupied a specific geographical area. In addition to this division, the Lenni Lenape were further divided into three subdivisions or "families" bearing the same names and totem insignia as those which apportioned the state, but had nothing to do with the area in which the people lived. Members of the "family" may have been required to marry outside their totem groups.

Each "family" was further divided into 12 clans, the exact nature of which has not been determined. Under this system, the territory occupied by "The People Who Live by the Ocean", the Unalachtigo, would have been divided into 36 areas: 12 for those whose totem was the Wolf, 12 for those whose totem was the Turtle, and 12 for those whose totem was the Turkey.

The clan possessed the land, but each individual owned his personal effects. The clans were named for some place where their ancestors had once lived, or for some characteristic peculiar to them. The clan had a chief who inherited the position through his mother. All children were born into their mother’s clan, not into the father’s.

Each of the three areas or nations into which New Jersey was divided had a chief or sachem, but there was no chief over the whole Lenni Lenape people. While it is not known just how it may have worked in actual practice, here is a breakdown of the nations, showing the political structure of the state under the Indian governmental system:

Top

The Nations

| Minsi Nation |

Unami Nation |

Unalachtigo Nation |

"People of the Stony County"

Totem -The Wolf

Chief of the Minsi Nation |

"People who live down River"

Totem -The Turtle

Chief of the Unami Nation |

"People who live by the Ocean"

Totem -The Turkey

Chief of the Unalachtigo Nation |

Minsi Family

Totem, the Wolf

12 Clans, each with a chief |

Minsi Family

Totem, the Wolf

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

Minsi Family

Totem, the Wolf

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

Unami Family

Totem, the Turtle

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

Unami Family

Totem, the Turtle

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

Unami Family

Totem, The Turtle

12 Clans, each with a chief |

Unalachtigo Family

Totem, the Turkey

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

Unalachtigo Family

Totem, the Turkey

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

Unalachtigo Family

Totem, The Turkey

12 Clans, each with a chief. |

These divisions tend to be somewhat confusing since the nations (or tribes) and the families bear the same names and totem insignia. A Lenni Lenape boy could have been a Unalachtigo because he lived in the southern division of the state. In addition, he could have belonged to the Unami family of the Tuekahoe Clan. While he lived in an area whose totem was the Turkey, his personal totem would have been the Turtle. It might also be noted that while the Turtle was shown in its entire form, the Wolf was represented by a print of its paw, and the Turkey by its foot

Top

Map of New Jersey

Showing Divisions. Totems. and Trails

Top

The Land of the Unalachtigo

All of southern New Jersey was covered with open forest. That is, there was little or no underbrush other than in the relatively few areas where the original forest had been destroyed by fire or hurricane. Such areas were easily avoided when hunting or traveling.

The territory occupied by the Unalachtigo was crossed by four major trails from the Delaware River to the ocean. The first, known as "The Old Cape Trail", originated at Trenton and ended near Somers Point. The second, beginning at Burlington joined the Cohansey Trail and continued to Cape May. The third started at Camden and ended near Toms River. The fourth, the "Cohansey Trail", began at Burlington and ran through what is now Camden, Gloucester, Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties.

All of southern New Jersey was covered with open forest. That is, there was little or no underbrush other than in the relatively few areas where the original forest had been destroyed by fire or hurricane. Such areas were easily avoided when hunting or traveling. The territory occupied by the Unalachtigo was crossed by four major trails from the Delaware River to the ocean. The first, known as "The Old Cape Trail", originated at Trenton and ended near Somers Point. The second, beginning at Burlington joined the Cohansey Trail and continued to Cape May. The third started at Camden and ended near Toms River. The fourth, the "Cohansey Trail", began at Burlington and ran through what is now Camden, Gloucester, Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties.

There were countless intermediate trails formed by the hunters and by the Indian people for the purpose of intervillage visiting. These trails were utilized as roads by the colonists when they settled the area. It was not until about the time for the Revolution that the roads of Cumberland County were sufficiently developed to permit the use of wheeled vehicles. Most travel by the early settlers was by horseback or by water.

Top

Lenni Lenape Food

Indian food was obtained by means of hunting, fishing, gathering, and farming. The extensive forests of southern New Jersey provided a large and varied assortment of game: deer, elk, bear, fox, raccoon, opossum, muskrat, beaver, squirrel and rabbit. These were either shot with bow and arrow or trapped, and they provided both meat and fur. Their pelts were used for clothing and to provide the thongs with which the stone implements were fastened to wooden shafts and with which their clothing was sewn.

The grassy meadows along the Delaware Bay and the water courses of the Cohansey and Maurice Rivers attracted huge flocks of ducks, geese and swan. Early records of the colonial period describe a species of migratory pigeon so plentiful that they broke down the limbs of trees on which they settled at night. Partridge, quail and woodcock abounded and the wild turkey, the totem of the Unalachtigo, was found in large flocks; each bird weighing from thirty to forty pounds.

The only domesticated animal owned by the Indian of New Jersey was the dog. The Indian dog was much like a wolf in appearance and was at no time considered to be a pet. He served to announce the arrival of strangers in the villages and as a scavenger in disposing of refuse; he sometimes accompanied the hunters in their search for bear or elk; and in the time of need he was used as a source of food. It has been said that there were many more dogs in each village in the fall than there were in the spring! Still another source of food in time of famine were the reptiles which abounded in the forests and swamps of Cumberland County.

Fish were caught with the aid of a weir, net, bow and arrow or club. The weir was a "V" shaped dam of stones with the point headed downstream Fishermen would start upstream and drag toward the weir either a brush net made by lashing branches together or a knotted net made of Indian hemp weighted down with notched stone sinkers. The fish were thus driven into the narrow opening of the weir or into shallow water where they were shot, speared, clubbed or caught with the bands.

Oysters, clams, crabs, mussels and other shellfish were gathered from the bay and dried or smoked over an open fire to prepare them for storage until winter use. The shells were sometimes pounded into a powder and used for tempering pottery. Certain shells were also used for making ornaments or wampum.

While living at the shore, the Indians set up temporary camps or shelters in wigwams covered with mats made of the reeds growing by the water. They returned to the same campgrounds every year, and piles of shells and camp refuse provide a source of many Indian artifacts for the present-day collector.

A large part of the Indian diet was gathered. Women and children gathered wild vegetable foods and fruits: persimmons, grapes, beach plums, huckleberries, cranberries, strawberries, blackberries, walnuts, hickory nuts, roots, and herbs. All were placed and carried in the baskets which Indian women were skilled in weaving from grass or thin strips of wood and bark. There was also an abundant supply of wild honey. The Lenni Lenape obtained maple sugar by boiling down the sap of the maple tree each spring.

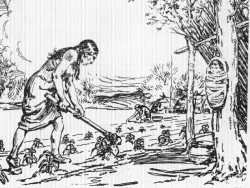

Gardens were placed immediately beyond the village compound and were cultivated by the women. The garden areas were cleared by girdling the large trees so they would die, and then planting the crops between them Each family plot included several types or varieties of corn, beans, pumpkins or squash, and tobacco. The beans were planted in the same hill as corn, so that the vines would be supported by the corn stalks. Fish was used as fertilizer. During the summer months the crops were cultivated with a crooked stick, crudely chipped stone hoes or the shoulder blade of a deer tied to a wooden shaft.

When planting his garden the Indian made no attempt to maintain rows or a pattern; each vegetable was planted wherever convenient between the stumps of the trees. In fact, to the Indian mind the orderly plantings of the white settler were unnatural and most unattractive. The Great Spirit did not plant trees in rows!

Much food was stored for winter use. Corn was parched by roasting the dried kernels over a fire and then placed in clay storage pots sunk into the ground or in pits lined with leaves and bark. Squash was cut strips, dried, and strung on poles which were then placed across the ceiling of their huts. Highly prized bear fat or grease was stored in skin bags.

Gathering and Smoking Shellfish Cultivating Corn With a Stone Hoe

Top

Shelter

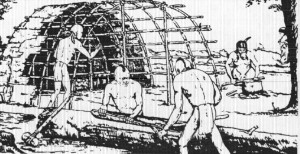

The Lenni Lenape did not live in the portable skin-covered teepee so often pictured as the Indian home. The most common form of shelter in the southern part of New Jersey was a rectangular house measuring approximately ten by twenty feet.

In building their homes the Indians drove saplings into the ground about two or three feet apart, outlining the size and the shape of the house. The slender tops of the saplings were bent and lashed together so as to form an arched or vaulted roof. Other thin saplings were tied crosswise over the upright poles to make the framework more secure. The frame was then shingled with large pieces of bark peeled with stone tools from elm, chestnut or cedar trees. The shingles were tied to the frame and chinked with clay or mud to make them weatherproof.

Inside the house raised platforms built around the walls provided a storage place beneath them, while the surface of the platform sewed as seats, tables, and beds. The walls were covered with mats made of reeds or rushes. Poles were fastened near the ceiling, and from them dried foods and other family possessions were suspended. There was an opening in the roof and under it was a fireplace consisting of a circle of stones.

The Unalachtigo village was always located near a stream or river in order that water for their bathing and cooking would be available and that their canoes would be near at hand.

Here in Cumberland County the villages were not surrounded by the stockades found necessary in less peaceful areas. A large council house was built in the center of what would become a village. The wigwams or homes of the individual family units were placed around it with no attempt to form "streets" or an orderly pattern of community design. Bath houses were constructed near the water’s edge; one for women and one for men. Steam baths were an important part of Indian life. Stones were heated in a fire and then carried to the bath house, where steam was produced by throwing water on the stones.

Building A Bark-Covered Wigwam

Building A Bark-Covered Wigwam

Top

Transportation

Land transportation was by foot. The Indian was a tireless traveler, and the state was divided not only by the major trails but also by countless smaller trails leading from one village to another, to favorite hunting grounds, or perhaps to a quarry where stone or clay might be found.

Snowshoes, an Indian invention, were used in the winter. Bundles were carried on the back, supported by a headband or tumpline drawn across the forehead. Babies were carried on a cradleboard on the mother’s back. The cradleboard could be hung on a nearby tree while the mother worked in the garden or gathered food from the forest.

Dugout canoes were used for water transportation in the territory occupied by the Unalachtigo. These canoes ranged from about 12 feet to 40 feet in length. The Delaware Indians did not use the lightweight birch bark canoes of the northern Indian. This was no doubt partially due to the fact that in the southern part of New Jersey travel was accomplished on the slow-moving tidewater of the streams and bay, The far greater durability of the dugout justified the expenditure of effort required to build it.

The method of making a dugout canoe illustrates the effort and determination expended in the accomplishment of Indian craftsmanship. First, a sufficiently large tree must be felled. This was achieved by burning a section near the base of a standing tree, removing the charred portion with a stone axe and repeating the slow process until the tree fell. The interior of the log was hollowed out by placing burning coals upon the surface to be removed. As the wood burned, the charred fragments were scraped away with a stone adze or gouge. When the desired inside space was obtained, the outside bark was removed and the canoe completed by forming the pointed bow and stem.

Constructing a Dugout Canoe

Constructing a Dugout Canoe

Top

Pottery

Lacking metal cooking utensils until after the Europeans settled in Cumberland County, the clay pots made by the Indian women were among the most highly prized possessions of each family.

Because the pottery was so fragile, it was rarely taken on camping expeditions or even when the family moved to the shore for a season of fishing or the gathering of shellfish.

Therefore, the finding of pieces of broken pottery is an almost certain indication that an Indian village was once located on that site.

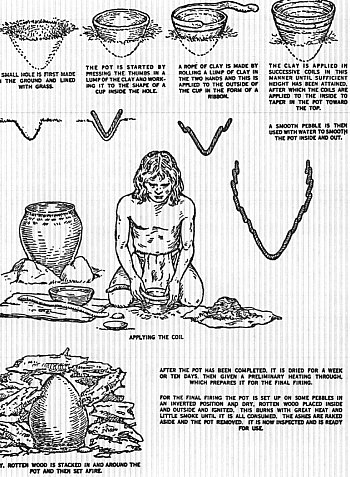

In preparing to make a vessel the clay was carefully cleaned of pebbles and sticks before being kneaded with enough water to achieve the proper working consistency. Crushed stone or shell was mixed with the clay to act as a tempering agent which then prevented the pot from cracking while being fired.

After kneading, the pliable clay was rolled into the form of a rope which was then coiled, layer upon layer, to form the desired shape of the vessel. The bottom of the pot was conical in shape. This was achieved by digging a small hole in the ground, lining it with soft grass and then starting the coil in the base of the hole gradually enlarging the diameter of the pot as each successive row of clay was added.

When the pot was sufficiently large, the surface was smoothed and the exterior decorated by covering it with impressions of cord or net or by drawing geometric designs on it with a pointed stick or bone. The mouth of the vessel was often finished by pressing a rounded stick into the surface of the edge.

The clay pot was placed in the sun until it dried and was then fired by partially filling it with hot coals and by building a fire of dry wood around it. Making pottery was the responsibility of the women and it is evident great pride was taken in the performance of this aspect of Indian art.

An indication of the value placed upon the pottery is shown by finding pots which have cracked with use, but have been mended by boring holes on either side of the crack in order that it might be tied together with strands of sinew after the crack bad been filled with soft clay or pine pitch. The pot could then continue to be used for the storage of dry materials.

Today much broken pottery is found in surface bunting or is located by poking around in a wooded area near a known campsite with a steel probe which has been attached to a wooden cane. The ground is screened, picking out pieces of potsherds and fragments of the broken bowls. When they have been fitted together and glued into place they yield a restored clay pot.

Clay pots were used only for cooking or the storage of food. The Indian rarely made bowls or other vessels from clay. Food was served in bowls fashioned from wood, gourds, or tortise shells. Ladles to transfer the food from the cooking pot to the bowls were either carved from wood or were the necked variety of gourd so easily adapted to this use. Shells or wooden spoons were sometimes used as eating utensils.

Top

Tool Making

While the Indian women were occupied with weaving, gathering, cultivation of the gardens, and pottery making, the men, in addition to hunting and fishing, manufactured the weapons, tools, and implements used in their everyday life.

Flint or other stone used in the making of arrowheads, spearheads, axes, or pestles was not native to southern New Jersey and was obtained either by trading with other tribes or by traveling long distances to an area in which it might be found in plentiful supply.

The single exception to the above is the Cohansey or Greenwich Quartzite found in the vicinity of Greenwich and which was highly prized by the Unalachitigo of Cumberland County. Materials which were to be shaped were buried for a period of time in the belief that the stone could be more easily and accurately formed if it were freshly taken from the earth.

Caches of partially finished arrowheads have been found, indicating that the maker had accumulated a store of tips for his arrows, needing only the finishing touches to prepare them for use. The edges of the arrowheads and spearheads were flaked or chipped to produce the sharp cutting edge needed to penetrate the skin of the animal which was being bunted.

Reeds or young shoots of trees were used to form the shaft of the arrow. The stone tip was fastened to the shaft with sinew and fib glue. The material from which a spear shaft was made was obtained by splitting a tree trunk, seasoning the strips of wood, and then painstakingly rounding and smoothing them to form the shaft and to insure accuracy when thrown. A specially grooved stone was used in smoothing and shaping the spear shaft.

Celts, axes, gouges, pestles, and the adze were made of porphyry, granulated quartz, sandstone or similar materials; stone which could be used for pounding without shattering or breaking into smaller pieces. While these materials could not be flaked to produce a cutting edge, they were ground and beveled with a harder rock to shape them for the intended use.

The mortar used with the pestle for grinding corn or other foods was sometimes made of stone, but ordinarily consisted of a tree stump or piece of log hollowed out by the same process used in the construction of the dugout canoe.

Still another pastime with which the men were engaged, was that of making wampum from the shell especially gathered for this purpose. To form each bead of wampum required many hours of careful cutting and drilling with the primitive equipment of the Indian.

Top

The Departure Of The Unalachtigo

Within 150 years after their first real contact with the white man, there were almost no Indians left in Cumberland County. In 1638 the Swedes established hunting camps along the Wahatquenak (Maurice) River where it has been recorded they killed thousands of geese for their feathers. In the first year of Swedish trading with the Unalachtigo of Cumberland County 30,000 pelts were shipped to the fur markets of Europe.

As game became increasingly scarce many of the Unalachtigo moved to Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland where the heavily wooded land offered better opportunities for bunting.

With the arrival of the colonists came many changes to the Indian way of life. Stone axes were replaced with the much more efficient iron axe and adze. A canoe could be made in a fraction of the time formerly required to laboriously chip away the charred bits of wood to fashion the dugout used by the Unalachtigo. Guns for hunting were greatly sought after, but because the powder was expensive and difficult to obtain, triangular arrowheads were made from bits of sheet metal. These were more easily worked than the stone formerly used.

Women gladly gave up the chore of making their fragile pottery in favor of using the sturdy iron pots in which they might cook their food without danger of breakage. The durable, comfortable clothing made from deer hide was replaced by the women who coveted the long skirts and blouses worn by their white neighbors. Soon after contact with the colonists, Indian mothers abandoned the cradleboard, in spite of its convenience. Men in turn, adopted trousers and hats like those worn by the traders.

With the arrival of the pioneers came the introduction of sicknesses that were fatal to the Indian. Later, one of them bitterly said that for every white man who settled in this area six Indians died. Hundred of adult Indians died from illnesses we call "childhood diseases" such as measles, chickenpox and mumps. They were especially susceptible to smallpox and tuberculosis. The most powerful herbs and incantations of their medicine men were ineffective in the treatment of these diseases.

Another problem that caused equal difficulty was the introduction of rum and other alcoholic beverages. To the Indian anything that produced hallucination was considered to be of a spiritual nature and eagerly sought after. The intent was to get as drunk as possible, as quickly as possible and for as long as possible, in order to experience a continued sense of exaltation. Many Indians believed it to be desirable to die while under the influence of alcohol. Even though the colonial government restricted the sale of rum to the Indians, the old women of the tribe soon learned to make wine and hard cider for which they found a ready market among their people.

In their relationship with the white man, the Lenni Lenape relied upon debate and the settlement of differences in their councils. The Indian people were represented by orators who had spent long periods in training for this work. William Penn is credited with the statement: "be will deserve the name of a wise man that can outwit them." In a letter dated 1683 William Penn wrote that no tongue spoken in Europe could surpass the language of the Lenni Lenape in melody or in grandeur of accent and emphasis.

In 1758 an act was passed by the government of New Jersey guaranteeing the Indians the perpetual right to hunt on any unfenced land and to fish in the rivers and bays. The Indians were at this time compensated for lands they had once occupied.

Hers in Cumberland County the following was recorded in 1869 by Judge Lucius Q. C. Elmer in his "History of Cumberland County": "At a conference held by the commissioners appointed by the legislature with the Indians in 1758, one Robert Kecot (an Indian) claimed the township of Deerfield where the Presbyterian meeting house stands, and also the tracts of James Wasse, Joseph Peck, and Stephen Chesup. After this, all the Indian claims were fully paid for and relinquished. A few of these original inhabitants lingered within the county until after the Revolution, earning their subsistence principally by making baskets."

As a part of the negotiations with the Lenni Lenape in 1758, a tract of 3,384 acres of land in southeastern Burlington County, known as Edge-pilloc, was purchased for use as an Indian reservation. With high hopes for its success, Governor Bernard named the community which was to be established, "Brotherton".

The Rev’d John Brainerd. a Presbyterian who bad been commissioned as a missionary by ‘The Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge" who had their headquarters in Scotland, was appointed superintendent of the reservation and worked among the Indians until 1777. In failing health and as the result of the destruction of his church and home in Mt. Holly by the Tories, John Brainerd came to the village of Deerfield Street where he served as pastor until his death in 1781. While at Deerfield Street he continued his oversight of the reservation in Brotherton, which is now known as Indian Mills.

Although comfortable homes, a meeting house and a mill Had been provided for the Indians at Brotherton, as well as attempts made to teach them useful crafts, the colony was not a particularly successful venture. In 1801 the remaining sixty-seven adult Lenni Lenape decided to accept the invitation of the Mohicans to join them on their reservation at Oneida Lake in New York state. The land at Brotherton was sold and a portion of the proceeds used to transport the tribe to Stockbridge Reservation; the balance was invested for their later use.

After several years at Stockbridge the Lenni Lenape, now reduced to forty members, decided to move west to Wisconsin. The New Jersey government used the balance of the funds remaining from the sale of Brotherton to move them to this new location.

After moving to Wisconsin, the tribe sent one of their people, known as Bartholomew S. Calvin, son of the native schoolmaster who bad served in Brotherton during the days of John Brainerd, to negotiate for the sale of the Hunting and fishing rights guaranteed them in 1758. In his presentation of the request, "Wilted Grass" prefaced his plea with these words, so reminiscent of the beauty of phrasing for which the language of the Lenni Lenape was known: "I am old and weak and poor, and therefore a fit representative of my people. You are young and strong and rich, and therefore fit representatives of your people." It is to the eternal credit of the legislators of our state that the request was heard with both sympathy and consideration.

When the desired payment for the hunting and fishing rights had been granted, Bartholomew S. Calvin, expressing appreciation in behalf of his people, made the following statement which should be cherished and known by the people of New Jersey:

"Not a drop of our blood have you spilled in battle; not an acre of our land have you taken but by our consent. These facts speak for themselves and need no comment. They place the character of New Jersey in bold relief, a bright example to those states within whose limits our brethern still remain. Nothing save benisons can fall upon her from the lips of a Lenni Lenape."

Upon the completion of this transaction which occurred in 1832, the pages of the history of the. Lenni Lenape in New Jersey came to a close. All too little tangible evidence remains of the presence of the Unalachtigo in Cumberland County other than the exhibits of artifacts such as those contained in the collection made by George J. Woodruff.

To the Unalachtigo the land he knew by the name of Shayakbee (a long strip of land extending into the water) could provide ample space for coexistence with the fair people who came in their great canoes from Europe. He bad no way of visualizing a way of life other than that which he bad always known, so he gladly shared his land with the white man who had no land. But, as each ship arrived with more white settlers, more land cleared and more fences built, there was simply less and less of his world remaining. At no time did he resort to violence to regain what had once been his own.

The presence of the Lenni Lenape in Cumberland County was so peaceful and unobtrusive there is little or no mention made of him in the records of the newcomers who made their homes in this area. Today the memory of the Indians who once roamed the quiet forests and streams of the land conveyed to John Fenwick in 1676 is primarily retained in the form of a few place names. However, there remains much to be learned of the nature of the original people of Cumberland County from a study of those specimens of their handiwork which have endured to the present as well as those artifacts which are yet to be discovered by both amateur and professional archeologists.

Top

Lizard Stone

This rare ceremonial object has been identified as a lizard stone;

an effigy made of chert, a sedimentary flint. The lizard stone was found in the vicinity of Cohansey.

Top

Clay Pots

a. Found near Marlboro. The markings were made with a sharp stick. This particular specimen has a large collar and has been decorated with an unusual chevron design.

b. Found in Fairton near Ramoh Road. The sweeping design was achieved by pressing rope into the soft clay before firing. The holes show where the broken pot had been mended. Preforations were drilled, the pieces bound together with sinew and glued with pine pitch. Such mended vessals were then used for the storage of dried foods.

c. This pot is of the shape and design most frequently found in southern New Jersey. There is a marked similarity in decoration to pots found in Mexico.

Top

Arrowhead and Spearhead

This triangular arrowhead is made of Cohansey Quartzite which quarried on the Robert Ewing farm in Greenwich. The long narrow fish spear is mode of brown flint.

Top

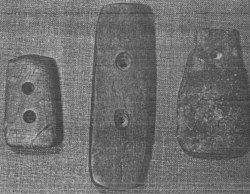

Grooved and Ungrooved Axe

The three-quarter grooved porphyry axe was fastened to a split stick and used for chopping or pounding. The celt or ungrooved axe was fastened on a handle which could be skipped off and the implement then used as a hand tool. This particular specimen is made of granulated quartz.

Top

Gorgets

The gorget was sometimes used as on ornament, to fasten back the hair, as fasteners or buttons on the loose shoulder robes worn during the winter, or as a guard to protect the wrist from the back lash of the bow string.

Top

Drill Points

The drill points illustrated are made of flint, jasper and quartzite and were used for drilling a hole in other materials. They were fastened on a wooden handle for leverage.

Top

Blade & Scraper

a. Made of brown flint with a sharp edge for cutting. Found at Three Bridges near Canton.

b. The scraper is completely flat on one side with sharp cutting edges for scraping fat from the hides of animals or for scaling fish.

Top

Net Sinker

This soapstone net sinker, with a complete groove, was used as a weight for either fish nets or a hand line.

Top

Banner Stones

The archaic ceremonial objects hove been carefully shaped. The perfect hole which was drilled with a hollow reed, sand and water may have taken up to 3,000 hours to accomplish. The bannerstone was used as a weight to produce thrust when throwing a spear It is believed to have been a prized possession of the chief of the tribe.

Top

Shaft Smoother

This is a rough stone with an abrasive quality need for the smoothing and straightening the shaft for anarrowor spear.

Top

Pestle and Mortar

a. The pestle is the pounding implement for grinding groin or herbs

b. The soapstone mortar is the container for the material being ground. Usually a wooden pestle was wed with a stone mortar or vice versa to ovoid ground-up sediment being mixed with the food.

Top

Bone Implements

a. The bone awl was the Indian woman's needle for sewing clothing and pulling strands apart when weaving.

b. The antler was used for flaking secondary chips and notching the points when making arrowheads and spearheads. These artifacts were found on the Riggins Farm and the Shoemaker Farm in refuse pits near former Indian villages. The greasy soil acted as a preservative in preventing absorption by the acid soil.

Top

Beads

a. These clay beads were found at Matt’s Landing near Port Elizabeth on the Maurice River. Found in a bed of charcoal, lying in a straight row. indicated that they hod been fired but never removed by the Indian woman who had made them.

b. The copper beads were found near Beasley’s Point during the excavation for a housing development. Deposits of copper have been found in northern New Jersey.

Top

Pipes

a. This clay pipe was found intact on the Riggins Farm.

Restored clay pipe found on the Riggins Farm. The Indians had propagated tobacco and introduced it to the first settlers.

Top

Acknowledgements

New Jersey’s Indians by Dorothy Cross, Report No. 1 published by New Jersey State Museum, Department of Education of New Jersey. Trenton, New Jersey. 1965, 1970. By permission.

History of the Early Settlement and Progress of Cumberland County, New Jersey by Lucius Q. C. Elmer. Published at Bridgeton, New Jersey by George F. Nixon, 1869.

South Jersey - A History, by Alfred M. Heston. Published by Lewis

Historical Publishing Company, Inc., New York and Chicago - 1924.

A History of Gloucester, Cumberland and Salem Counties by Cushing and Sheppard.

The photographs of representative items from the collection of George J. Woodruff were made by Richard King, Librarian of the Cumberland County Historical Society.

It is desired to record the appreciation of the Woodruff family to Howard Radcliffe of Bridgeton. New Jersey for his assistance in restoring the fifty-three individual pieced of pottery which form a part of the collection in the George J. Woodruff Museum.

Illustration of Pottery Making. The Indians of New Jersey Dickon Among the Lenapes by M. R. Harrington, Published by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey 1963. By permission.

Illustrations: Cultivating Corn with a Stone Hoe; Gathering and Smoking

Shellfish for Winter Use; Constructing a Dugout Canoe; Building a Bark -covered Wigwam. From a pamphlet published by the State of New Jersey. By permission.

Bulletins from Eastern States Archeological Federation. Bulletons from Archeological Society of New Jersey.

Top

Online Publication of this book courtesy of:

Cumberland County Library